Notes on

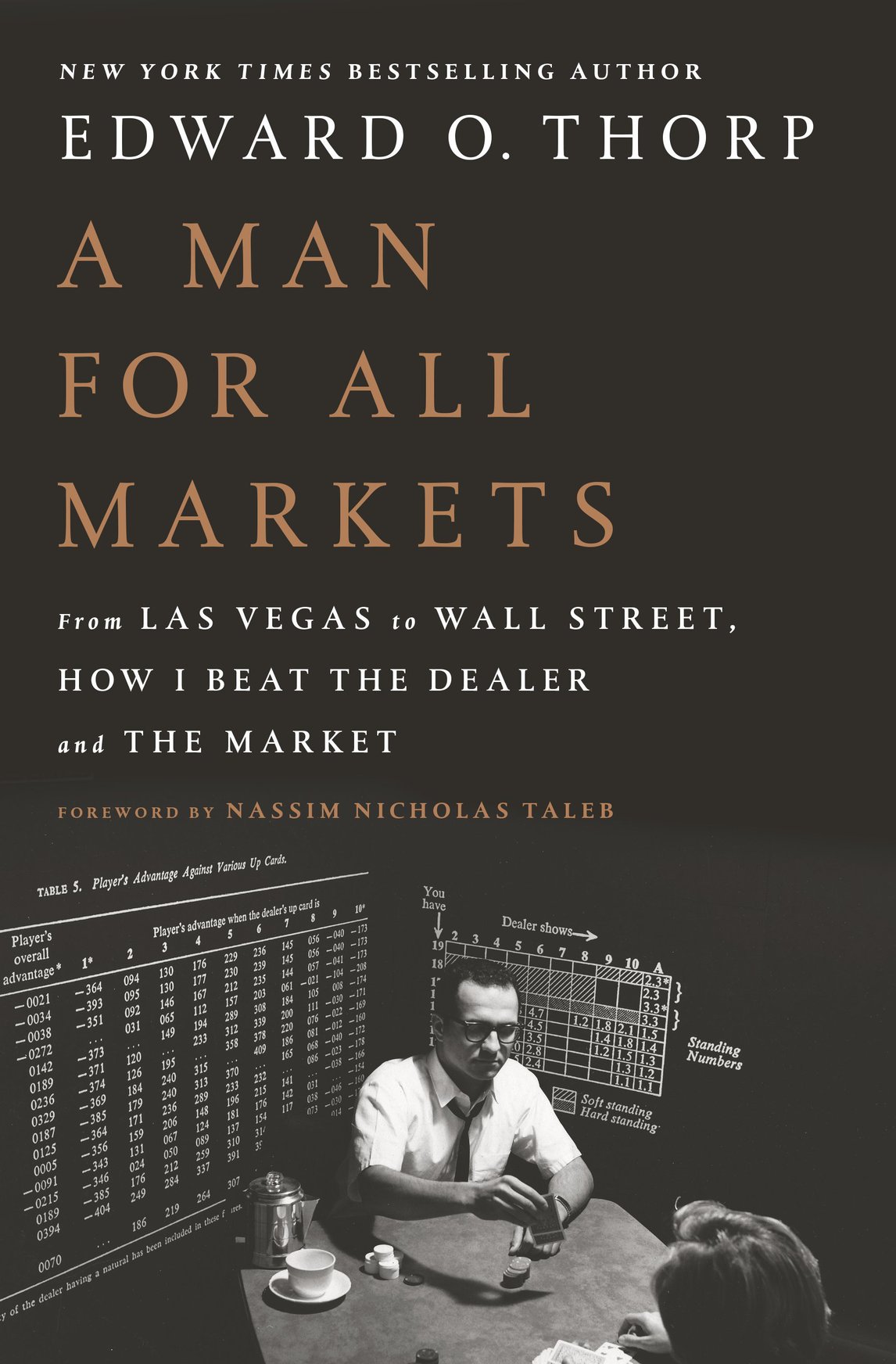

A Man for All Markets

by Edward O. Thorp

• 26 min read

Ed Thorp is a mathematician who figured out how to beat casinos, then figured out how to beat Wall Street.

I loved this book. The stories are incredible and the investing chapters are some of the best I’ve read.

The thread running through everything is his approach: find a clear edge, capture it with proper bet sizing, and don’t blow up.

He did this with blackjack, roulette, warrants, options, convertible bonds, and statistical arbitrage. But the book is also about knowing when to stop playing, and what “enough” looks like.

Thinking differently and self-learning

Thorp was largely self-taught, and he thinks that’s what gave him an edge. Not following the standard curriculum meant he questioned things others took for granted, like “you can’t beat the casinos.”

Though we didn’t have helpful connections and I went to public schools, I found a resource that made all the difference: I learned how to think.

He thinks in models, simplified versions of reality, like maps or physics simulations. He learned early that physical systems follow rules you can discover through experimentation, and those rules let you predict new situations.

Some people think in words, some use numbers, and still others work with visual images. I do all of these, but I also think using models. A model is a simplified version of reality…

I learned that simple devices such as gears, levers, and pulleys follow basic rules. You could discover the rules by experimenting and, if you got them right, could then use the rules to predict what would happen in new situations.

His approach boiled down to:

- Check widely accepted views for himself instead of trusting them.

- Test theories with experiments and apply pure thought profitably (e.g., warrant valuation).

- Set goals, make realistic plans, persist.

- Strive for consistent rationality, not just in one domain but in everything.

- Withhold judgment until evidence supports a decision.

Because of circumstances, I was largely self-taught and that led me to think differently… I strove to be consistently rational… I also learned the value of withholding judgement until I could make a decision based on evidence.

Not learning things the traditional way is an advantage. You end up with different thinking patterns than people who followed the standard path. Being an outsider looking in helps.

He also picked up a useful mental check after a classroom incident. Two questions to ask before acting, especially when emotions are running high:

- If you do this, what do you want to happen?

- If you do this, what do you think will happen?

Finding and capturing an edge

Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s foreword is full of praise for Thorp. He calls him the first modern mathematician to successfully use quantitative methods for risk-taking and actually make money doing it. The “dean” of quants.

Taleb frames Thorp’s method as two steps:

- Identify a clear edge. It has to be obvious and uncomplicated. Put the long-term odds in your favor.

- Capture the edge. This is the hard part — converting a theoretical edge into actual money. Bet sizing matters. Not too much, not too little.

It is capturing the edge, converting it into dollars in the bank, restaurant meals, interesting cruises, and Christmas gifts to friends and family — that’s the hard part. It is the dosage of your betting — not too little, not too much — that matters in the end.

Thorp held this belief his entire career.

I also believed then, as I do now after more than fifty years as a money manager, that the surest way to get rich is to play only those gambling games or make those investments where I have an edge.

Simplicity and academia vs. practice

Taleb contrasts Thorp’s practical approach with how academics operate. Academics favor complexity because it gets citations and status. A mouse giving birth to a mountain.

Practitioners with skin in the game want the opposite: distill complex research into the simplest possible strategy.

When you reincarnate as practitioner, you want the mountain to give birth to the simplest possible strategy, and one that has the smallest number of side effects, the minimum possible hidden complications. Ed’s genius is demonstrated in the way he came up with very simple rules in blackjack. Instead of engaging in complicated combinatorics and memory-challenging card counting (something that requires one to be a savant), he crystallizes all his sophisticated research into simple rules… It is mentally easy… and such a strategy is immediately applicable by anyone with the ability to tie his shoes or find a casino on a map.

Thorp’s simple derivation of the option pricing formula (before Black-Scholes) wasn’t recognized at first, probably because it didn’t look sophisticated enough. Actually incredible. He had the same formula years before Black and Scholes rigorously proved it.

Taleb also notes that economists initially rejected Thorp and Kelly’s practical ideas, preferring grand general theories.

Strategies that allow you to survive are not the same thing as the ability to impress colleagues.

This makes me ask: how much am I just following the mainstream of ideas? What could I be paying attention to, but am not because others aren’t?

Being able to identify thinkers like Thorp and Kelly, people who prioritize effectiveness over conformity, is worth the effort.

Avoiding ruin and the Kelly Criterion

Avoid ruin. At all costs.

Having an edge is useless if you blow up before you can realize it. Both Thorp and Taleb hammer this point.

Having an “edge” and surviving are two different things: The first requires the second. As Warren Buffet said: “In order to succeed you must first survive.” You need to avoid ruin. At all costs.

The Kelly Criterion is a mathematical framework for bet sizing. It maximizes long-term growth while avoiding ruin. In practice, you need the ratio of expected profit to worst-case return, dynamically adjusted one bet at a time.

The Kelly-Thorp method requires no joint distribution or utility function. In practice, one needs the ratio of expected profit to worst-case return — dynamically adjusted (that is, one gamble at a time) to avoid ruin. That’s all.

Thorp adapted Kelly’s 1956 paper for blackjack, roulette, sports betting, and later the stock market.

For roulette, Kelly even showed it was worth spreading bets across neighboring numbers: you trade a little expected gain for a large reduction in risk.

Kelly showed that someone following his system would, over time, almost certainly end up wealthier than anyone using a different approach.

- You generally avoid total loss.

- Bigger edge = larger bet.

- Smaller risk = larger bet.

However, it can lead to wild wealth swings, so most people bet half-Kelly or less. It may not suit short time horizons or very risk-averse investors.

When probabilities aren’t exact (i.e., investing, not casino games), use conservative estimates. Buffett’s concentrated betting style is consistent with Kelly thinking.

Life choices, independence, and “enough”

Taleb admires that after Thorp closed his fund, he didn’t start another mega-fund. He didn’t get sucked into managing huge amounts of other people’s money for the fees. He valued independence and peace of mind over scale.

True success is exiting some rat race to modulate one’s activities for peace of mind. Thorp certainly learned a lesson… You can detect that the man is in control of his life.

Know what you want and don’t get caught up in status games.

When working with Shannon on the roulette computer, Thorp considered whether to become a professional gambler or stay in academia. He chose academia.

I felt then, as I do now, that what matters is what you do and how you do it, the quality of the time you spend, and the people you share it with.

After PNP closed, despite the trauma and the billions in future wealth destroyed, Thorp and his wife Vivian embraced the freedom. They had enough.

When Princeton Newport Partners closed, Vivian and I had money enough for the rest of our lives… it freed us to do more of what we enjoyed most: spend time with each other and the family and friends we loved, travel, and pursue our interests… Success on Wall Street was getting the most money. Success for us was having the best life.

He tells the story of Joseph Heller at a billionaire’s party. Kurt Vonnegut asked Heller how it felt knowing the host made more in a day than Catch-22 ever earned. Heller said he had something the billionaire never could: “The knowledge that I’ve got enough.”

Conquering casino games

Thorp’s advantage play started by questioning consensus. Everyone “knew” you couldn’t beat the casinos. Mathematicians had proven no betting system could overcome a house edge in games of pure chance with fixed odds.

That proof was correct. But Thorp realized some games aren’t purely static.

One of the triumphs of mathematics had been to prove with a single theorem that all such systems must fail. Under fairly general assumptions, no method for varying the size of your bets could overcome the casino’s advantage.

Roulette: He believed physical prediction was possible, based on high school physics ideas. Friction and gravity slow the ball, the rotor’s motion is measurable, and equations could forecast where the ball lands. Noise was the limiting factor, but he didn’t think it was fatal.

He asked Feynman if it was possible to beat roulette. Feynman said no. Thorp was encouraged: it meant nobody had solved it yet.

If anyone knew whether physical prediction at roulette was possible, it should be Richard Feynman. I asked him, “Is there any way to beat the game of roulette?” When he said there wasn’t, I was relieved and encouraged.

Blackjack: The money wasn’t the draw. What got him was the idea that you could win just by sitting in a room and thinking.

What intrigued me was the possibility that merely by sitting in a room and thinking, I could figure out how to win.

The breakthrough was that unlike craps or roulette (without prediction), blackjack odds change as cards are dealt. The remaining deck shifts the edge between player and casino. Track the cards, bet more when the odds favor you, less otherwise. The casino wins more small bets; you win more big bets.

I realized that the odds as the game progressed actually depended on which cards were still left in the deck and that the edge would shift as play continued, sometimes favoring the casino and sometimes the player. The player who kept track could vary his bets accordingly.

He wrote to Roger Baldwin, who had published an early blackjack paper, and asked for his detailed calculations. Baldwin generously sent two large boxes of lab manuals filled with thousands of pages.

Just ask! People are more accommodating than you think.

Baldwin’s strategy was optimal when nothing was known about played cards, cutting the house edge to 0.62%, already better than the “expert” advice at the time. Thorp’s method went further by exploiting the changing odds.

He published his findings (“A Favorable Strategy for Twenty-One,” title suggested by Shannon) quickly.

When conditions are ripe, multiple people tend to make the same discovery independently (Newton and Leibniz both invented calculus; Darwin and Wallace both arrived at evolution). Once word spreads that a problem is solvable, others figure it out faster. Wait too long and someone else gets there first.

It is also common in science for the time to be right for a discovery… Five years before I did my blackjack work, it would have been much more difficult… Five years afterward… it was clearly going to be much easier.

Another reason to publish quickly is the well-known phenomenon that it is typically much easier to solve a problem if you know it can be solved.

When the frontier moves, people are quick to explore it. Always let yourself know problems are solvable (The Beginning of Infinity).

Playing the system took emotional discipline. He bet only at levels where he was emotionally comfortable and didn’t scale up until he was ready. This carried through his entire investment career.

This plan, of betting only at a level at which I was emotionally comfortable and not advancing until I was ready, enabled me to play my system with a calm and disciplined accuracy.

He noticed that winning systems produce a specific pattern: moderate losses punctuated by streaks of big wins. Bleed a little, win big occasionally. He’d see this again and again in gambling and investing.

The casinos responded badly. They barred him, cheated him (blatant second-dealing), and a gaming control board agent who was supposed to protect him was working for the casinos, not him. Regulatory bodies can be corrupt.

I felt satisfaction and vindication when the great beast panicked. It felt good to know that, just by sitting in a room and using pure math, I could change the world around me.

Rather than quit the field, I launched an army with Beat the Dealer.

He notes that beating blackjack is still possible (qualified yes), but you need to find games with favorable rules: never play at a table where blackjack pays 6:5 or 1:1 instead of 3:2.

Baccarat: Thorp and associates proved a winning system over several nights at the tables.

On the fourth night, the pit boss was suddenly friendly. Smiling, relaxed, pleased to see him. They volunteered coffee “with cream and sugar, just the way you like it.”

Partway into the shoe, winning and drinking his coffee, Thorp suddenly couldn’t think. Couldn’t keep the count. His pupils were hugely dilated. A nurse in the group recognized the signs immediately. He’d been drugged.

Then, on the drive home, their car’s accelerator jammed on a mountain road at 65 mph. A mechanic found a part had unscrewed from a threaded rod in a way he’d never seen and couldn’t explain.

Transition to Wall Street

After poor early results investing his blackjack winnings and book royalties, Thorp saw Wall Street as a bigger casino where his methods might work.

Could my methods for beating games of chance give me an edge in the greatest gambling arena on earth, Wall Street? Ever curious, I decided to find out.

The similarities are obvious. Math, stats, and computers for analysis. Risk/return tradeoffs for money management. Psychological parallels. Bet too much and you blow up (LTCM), bet too little and you leave money on the table.

Gambling is investing simplified. The striking similarities between the two suggested to me that, just as some gambling games could be beaten, it might also be possible to do better than the market averages.

He educated himself by reading classics (Security Analysis, technical analysis books) and filtering like a “baleen whale.” Once again, he was surprised by how little most market participants knew.

Early investing lessons and mistakes

His first stock pick was Electric Autolite, bought based on a story without understanding the business. Lost 50%.

He invested in something he didn’t understand (a diversified fund would’ve been better), and anchored to his purchase price, waiting years just to “get even” while ignoring opportunity costs. That’s a gambler’s fallacy applied to investing.

Focus on fundamentals and alternatives, not your personal price history. “Most stock-picking stories, advice, and recommendations are completely worthless.”

He also looked into momentum and charting. Technical analysis seemed worthless. As Vivian said about a chartist they knew: “Just look at his worn-out shoes.”

His silver investment had the right economic analysis (silver would rise), but excessive leverage wiped him out. Margin calls forced selling during a dip, pushing prices down further, triggering more forced sales.

A few thousand dollars bought him a lesson he’d apply for the next fifty years. Manage your risk and watch your leverage.

He also learned the principal-agent problem. Beware when your salesman’s interests don’t align with yours.

Warrants, options, and hedging

Thorp discovered warrants (the right to buy stock at a set price by a deadline) and realized their prices tend to move with the underlying stock. This led to hedging:

- Find two related securities that are relatively mispriced (e.g., warrant and stock).

- Buy the underpriced one, short sell the overpriced one.

- Choose proportions so price fluctuations cancel out most of the risk.

- Profit when the mispricing corrects.

To form a hedge, take two securities whose prices tend to move together… Buy the relatively underpriced security and sell short the relatively overpriced security… If the relative mispricing between the two securities disappears as expected, close the position in both and collect a profit.

He worked with Sheen Kassouf. Thorp preferred neutral hedges, minimizing risk regardless of market direction, because of his bad stock-picking experiences. Kassouf, an economist, was willing to deviate based on company analysis.

Thorp shared his findings publicly. “I would continue to have more ideas.”

Option pricing: In 1967, Thorp developed a practical formula for warrant/option valuation. Existing academic formulas required estimates for unknown future stock growth rates and risk discount factors, making them unusable. Thorp reasoned intuitively that both unknowns could be replaced by the risk-free interest rate (e.g., the T-bill rate).

Using plausible and intuitive reasoning, I supposed that both the unknown growth rate and the discount factor… could be replaced by the so-called riskless interest rate… This converted an unusable formula with unknown quantities into a simple practical trading tool.

It worked spectacularly. Unknown to Thorp, Fischer Black and Myron Scholes rigorously proved the identical formula shortly after, publishing in 1972-73. This became the Black-Scholes(-Merton) model.

The history traces all the way back to Bachelier’s 1900 thesis and even Einstein’s Brownian motion work, which used similar math.

When the CBOE opened in 1973, Thorp had his formula programmed and was visualizing mispricings. Then Fischer Black sent him a preprint of the same formula. It was now public, but the rigorous proof confirmed his intuition.

Adoption took time, so PNP still had an initial edge. “Like firearms versus bows and arrows.”

Thorp had already extended the model beyond basic Black-Scholes to handle dividends, short-sale restrictions, and American put options (exercisable anytime, unlike European options). No general formula for American puts exists even today. He used a numerical “integral method” to value them.

Convertible bonds

Bonds that can be converted into a fixed number of shares of the company’s stock. Their price has two parts:

- Value as a regular bond (interest payments, principal repayment) — sets a price floor.

- Value of the conversion option — increases if the stock price rises above the conversion threshold.

Companies issue them because the conversion feature lets them pay a lower interest rate. Thorp used these in hedging strategies.

Princeton Newport Partners and quantitative investing

PNP, founded in 1969, specialized in hedging convertible securities: warrants, options, bonds, preferreds. They took hedging to an extreme nobody had tried before:

- Designed individual hedges to minimize risk from stock price movements in either direction.

- Hedged against interest rate changes, overall market shifts, and catastrophic tail events.

- Relied almost entirely on quantitative methods: formulas, models, computers. Among the earliest “quants.”

Hedging risk was not new but we took it to an extreme never before tried… This nearly total reliance on quantitative methods was unique, making us the earliest of a new breed of investors who would later be called quants…

Risk management: PNP’s approach contrasted with the later widespread use of VaR (“value at risk”). VaR estimates damage from the most likely 95% of outcomes but ignores the extreme 5% tail — and that’s where ruin lives.

The defect of VaR alone is that it doesn’t fully account for the worst 5 percent of expected cases. But these extreme events are where ruin is to be found.

Stress-testing against past crises is also not enough. A major quant fund tested against 1987, LTCM, Katrina, and more, and found a 4% max loss on their portfolio. They actually lost over 50% in 2008-09 because the credit collapse was different in kind from anything they’d simulated.

Testing against outliers in the past is fine, but if you think that is sufficient caution against future outliers, you’re missing the point. Why do you think the future outliers will resemble past ones?

PNP took a broader view. They analyzed tail risk and asked extreme “what if” questions. “What if the market fell 25% in one day?” More than a decade later, it did exactly that, and PNP was barely affected.

When they moved to Goldman Sachs, Thorp asked what happens if a nuclear bomb hits New York. Goldman said they had duplicate records stored underground in Iron Mountain, Colorado.

It’s hard to imagine every scenario. But you have to try.

Investment strategies PNP developed:

- Convertible/option hedging models.

- Statistical arbitrage (MIDAS, later STAR): computerized systems finding temporary mispricings.

- Interest rate arbitrage group (ex-Salomon Brothers guys).

- MIDAS: stock prediction combining factors like earnings yield, dividend yield, book/price, momentum, short interest, earnings surprise, insider trading, sales/price.

- OSM Partners: a fund of hedge funds.

Black Monday (1987): The 23% one-day crash shocked most people, especially academics whose lognormal models said it was basically impossible. Thorp, aware the models underestimated tail risk, was less surprised.

He believed the cause was portfolio insurance, a strategy that sells stocks into declines to “protect” investors. The selling triggered more selling in a feedback loop. The cure became the cause.

PNP’s hedging protected them; they were largely unaffected.

It can be dangerous to rely on academic models. They aren’t built for survival. You want to survive. To keep playing.

PNP’s legacy: Citadel Investment Group was built on the PNP model. Ken Griffin started by trading options and convertibles from his Harvard dorm room. Thorp was Citadel’s first LP and shared PNP’s workings with Griffin.

Citadel grew to manage $20 billion with 1,000+ employees. Shows what PNP might have become.

Market inefficiency and the EMH

Thorp doesn’t buy the Efficient Market Hypothesis. His entire career (blackjack through quantitative finance) is a counterexample.

We didn’t ask, Is the market efficient? but rather, In what ways and to what extent is the market inefficient? and How can we exploit this?

That’s a much better question. And it goes back to where I have an edge.

He points to case after case where markets clearly aren’t rational:

- Madoff: Thousands of sophisticated investors fooled for decades. How can markets be efficient if massive fraud goes undetected by the “rational” crowd? Basically: how can everything be priced in when people can get fooled for decades.

- EMLX hoax: Stock crashed 60% in 15 minutes on false information, then failed to recover even after the hoax was exposed. If markets efficiently incorporate information, why didn’t it snap back?

- Teenage pump-and-dump: A 15-year-old manipulated thinly traded stocks via internet chat rooms and made $273,000. “Rational” investors bid up prices on fortune-cookie-quality tips. Reminds me of all the crypto discords promising “signals” on coins that would “go to the moon.”

- Dominelli Ponzi scheme: $200 million fraud Thorp detected early by simply checking for actual trading activity. There was none. Always check the underlying fundamentals. Can they prove they’re doing what they say? Don’t fall for hype.

- HFT: Some exchanges let high-frequency traders peek at orders 30 milliseconds early. How is that different from front-running? Thorp makes a good case that it’s predatory and extracts wealth from ordinary investors without creating social value.

- Media noise: Financial reporters write headlines like “Stocks Slump on Earnings Concern” for a 0.03% decline, a change that happens 97% of trading days. People see patterns and explanations where there aren’t any.

Eugene Fama, father of the EMH, once called a critic a criminal at a UCLA conference and said “GOD knew that the stock market was efficient.” He added that the closer you get to behavioral finance, the hotter you can feel the fires of Hell.

Yeah, invoke god in your theories. That’ll convince me.

Thorp contrasts the idealized EMH conditions with reality:

| Feature | EMH expectation | Market reality | How to beat it |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information | Instantly available to all | Spreads in stages; early access is key | Get good information early |

| Rationality | Participants largely rational | Limited rationality; emotional biases common | Be disciplined and rational; avoid emotion |

| Analysis | Everyone evaluates info instantly | Ability and time vary widely | Find superior analysis methods |

| Price action | Jumps instantly to new fair price | Often gradual adjustment | Invest ahead of the crowd |

For most people without a demonstrable edge, the market appears efficient — just like casino games appear random to those without a system. But for those who meet the conditions above, it’s beatable.

The EMH is a theory that can never be logically proved… it can be disproven merely by providing examples where it fails… Our portrait of real markets tells us what it takes to beat the market.

His advice is to focus within your circle of competence. Make sure your information is current and accurate. Understand the information food chain (first people to act eat; latecomers get eaten). Only bet when you have a real edge.

Statistical arbitrage (MUD / STAR)

A key strategy for PNP and later ventures.

MUD: PNP’s indicators project found that stocks which had gone up most in the prior two weeks tended to underperform, while the biggest losers tended to outperform. Buying the losers and shorting the winners yielded ~20% annualized historically. The portfolio was roughly market-neutral but still volatile.

Bamberger’s refinement: Gerry Bamberger at Morgan Stanley (probably building on similar research) developed a less volatile version, trading industry groups separately.

STAR: Thorp improved further using factor analysis. This statistically neutralized the portfolio not just to the market but to various factors (industry groups, interest rates, inflation, etc.) by ensuring long/short exposures cancelled out. Reduces risk, though also tends to reduce return. Barra confirmed STAR’s returns weren’t just factor luck.

D.E. Shaw: David Shaw, ex-Morgan Stanley quant, planned a similar fund. PNP considered backing him but passed since they already had STAR. Shaw built a hugely successful firm using stat arb as a core.

One of his hires was Jeff Bezos, who conceived Amazon while working at Shaw. If Shaw had partnered with PNP, we might not have Amazon.

Stat arb has capacity limits. Trading affects prices, eroding the mispricing. Also why the Medallion Fund can’t just produce infinite money.

Investing advice

These are some of the best chapters in the book.

For most people: index. Active investors as a group must match the market before costs. They pay higher fees and trade more, so they must underperform after costs, on average. Buying a low-cost index fund is the easiest way to outperform most other investors. In contests, random portfolios hold their own against expert picks.

Call any investment that mimics the whole market… “passive”… If these passive investors together own, say, 15 percent of every stock, then “everybody else” [active investors] owns 85 percent and, taken as a group, their investments also are like one giant index fund… The average active investor pays higher fees and commissions and trades more frequently, incurring taxes sooner… He loses to the passive index investor by the total extra amount paid.

Tax-exempt entities should seriously consider switching from active management unless they have compelling evidence of a real edge. That evidence is rare.

Asset allocation: Historically, stocks and income-producing real estate have offered the best long-term returns, with higher volatility. Diversifying between them helps. Chasing returns (buying high, selling low) hurts. Contrarian rebalancing (buying low, selling high) tends to outperform.

If you must pick stocks:

- Use valuation metrics like earnings yield (E/P, the inverse of P/E) to gauge attractiveness. Compare stock earnings yields to bond yields to guide allocation shifts.

- Be wary of compelling stories. Always ask: at what price is this a good buy? Set a buy price with a margin of safety. Act only when stocks are attractive.

- Understand taxes. Use tax-loss selling and tax-gain deferral. The leverage lesson from the 2008 real estate crisis: assume the worst imaginable outcome and make sure you can tolerate it.

- Avoid behavioral pitfalls: anchoring, chasing performance, focusing on income instead of total return, emotional decisions.

Negotiation and decision-making

Don’t push negotiations to the limit. A small extra gain isn’t worth the risk of breaking a deal. Make deals good for both sides. Relationships matter.

The same applies to trading. Constantly pushing for tiny price improvements (like an extra eighth of a point) might save small amounts frequently but risks missing large gains if the opportunity moves away.

Thorp asked traders if they could prove their scalping was net positive. None could.

There’s also the question of how hard to optimize. Maximizers seek the absolute best deal regardless of time and effort, which leads to stress. Satisficers accept “good enough” while factoring in search costs and the risk of losing near-optimal options. Don’t spend hours chasing the optimal deal if the ROI isn’t there.

The “secretary problem” in math illustrates this. Say you’re interviewing candidates and you have to accept or reject each one on the spot, no going back. The optimal strategy is to reject the first ~37% outright, using them to calibrate, then hire the next person who’s better than anyone you saw in that first batch.

If you commit too early, you don’t know what “good” looks like yet. Wait too long and the best candidate is probably already behind you. 37% (technically

Cognitive dissonance is another trap. People reject information that contradicts strongly held beliefs. Explains why Madoff investors ignored red flags for years.

And be careful with crowd wisdom. Averaging many guesses works for estimation problems (beans in a jar). But for binary choices (fraud or genius), the crowd can be catastrophically wrong if consensus forms around the wrong answer. Polling everyone isn’t always wise.

Education, health, and time

Thorp credits his education in math and science for teaching him to reason logically, build models, and predict outcomes. But the bigger lesson was learning how to learn and teach himself, because there weren’t any courses on beating blackjack or launching a market-neutral hedge fund.

Education builds software for your brain.

He wants basic probability and finance taught in schools. Understanding compound interest, managing debt, making better decisions.

The marshmallow test is a good example. A psychologist offered four-year-olds one marshmallow now, or two if they could wait twenty minutes. About a third waited. When evaluated at age twelve, the kids who waited were markedly higher achievers.

If you’re gobbling all your marshmallows now and carrying credit card debt at 16-29%, the first investment advice is to pay it off.

He spends 6-8 hours a week on fitness and thinks of each hour as one day less in a hospital.

He hires people to do things he doesn’t want to do, buying back time with money. You’re always converting between health, wealth, and time. Thorp is deliberate about which direction the conversion goes.

Life is like reading a novel or running a marathon. It’s not so much about reaching a goal but rather about the journey itself and the experiences along the way.

Best of all is the time I have spent with the people in my life that I care about… Whatever you do, enjoy your life and the people who share it with you, and leave something good of yourself for the generations to follow.

Liked these notes? Join the newsletter.

Get notified whenever I post new notes.