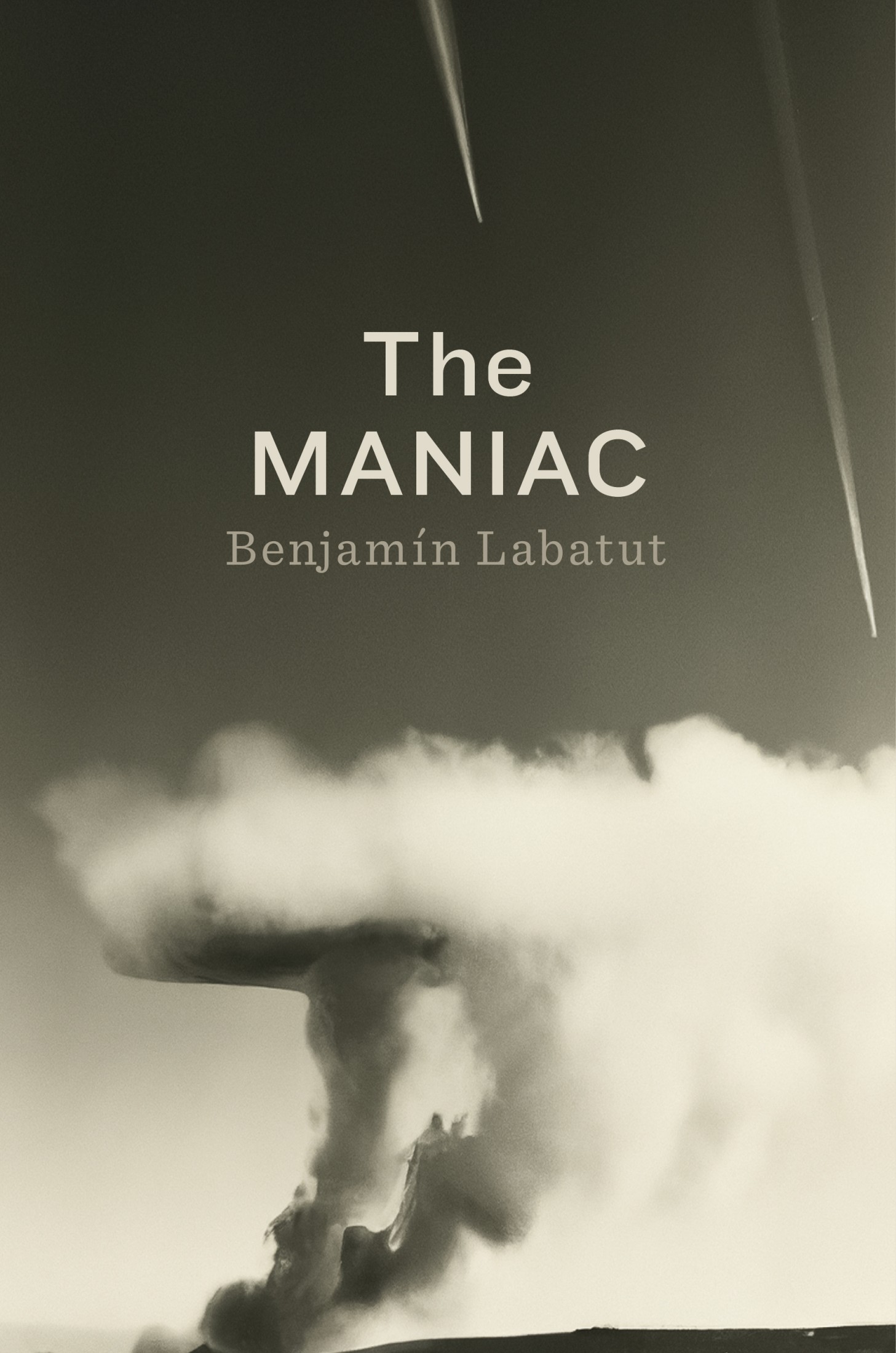

Notes on

The MANIAC

by Benjamín Labatut

• 7 min read

This book is fiction based on fact. It’s a real page-turner for sure. I really enjoyed it.

It started with Paul Ehrenfest taking his own life and killing his disabled son, so others wouldn’t have to take care of him. He went mad because he lost touch with his field.

Then it focuses on John von Neumann, the genius behind e.g. Game Theory, the first programmable computer, and so much more. There’s obviously a lot to admire, but the stories often paint him as inhuman due to his intellect or cold logical judgment.

The third part is about Lee Sedol and AlphaGo.

Given that this book is fiction based on fact, my notes regard the material that the book presented, not the true stories behind it. Do not take it as fact.

John von Neumann was born as Neumann János Lajos.

He displayed extraordinary intellectual abilities from a young age.

He was considered by peers to be one of the most brilliant minds of his time.

Von Neumann’s work laid foundations for modern computing, AI, and self-replicating systems.

His ideas continue to influence various scientific fields and philosophical discussions about technology’s role in society.

Chess and Game Theory

This (fictional) quote is Oskar Morgenstern talking with JvN about games & chess.

While we talked, we slowly drifted to the corner of the living room where Oppenheimer and Wigner were deeply absorbed in a game of chess, and I told Johnny that I had just read his 1928 paper “Theory of Parlor Games.” Did it, I asked, apply to something like chess? He gave a spirited twirl to his propeller before answering: “No, no, no! Chess is not a game! It is a well-defined form of computation. You may not be able to work out the correct answers because of its complexity, but in theory there must be a solution, an optimal way to play, a perfect move for any given position and configuration of pieces on the board. Now, real games are not like that at all. Games in real life are very different. To win in reality you must lie and deceive. The games that I’m interested in consist of carefully elaborated tactics of deception—of self-deception even!—so you have to be constantly asking yourself what the other man is thinking, how you will respond, and what he thinks that you are going to do next. That is what games are about in my theory.”

This makes me think of chess engines like Stockfish or AlphaZero .

Computer chess engines build, search, and evaluate massive trees that represent possible moves from the current position to find the most optimal move to make.

The amount of legal positions in chess is massive. Claude Shannon calculated the game-tree complexity to be

Solving chess would mean to find the optimal strategy such that one of the players can always either win or draw.

No complete solution currently exists, and many experts are pessimistic that we may not find one. I am not.

The distinction between chess and ‘real’ games is interesting, referring to game theory: the study of how (and why) we make decisions within a competitive context with opponents who are also making decisions.

Chess is deterministic and fully observable. What you see on the board is what there is. Most real-life scenarios are not. They include uncertainty and deception, whether intentional or not.

Chess offers comfort and respite from the uncertainty of real-life games. This is part of what makes it fun. We try to become good at this kind of game by approximating, in our own way, the optimal strategy.

von Neumann Probes

This is a “a self-building, self-repairing, and self-improving spacecraft that we could launch to colonize the outer planets of our solar system, and from there, blast off toward the darkest reaches of space.”

They mimic features of living organisms.

Whether it is fortunate or not, self-replicating machines and von Neumann probes remain beyond our reach. Creating them requires great leaps in miniaturization, propulsion systems, and advanced artificial intelligence, but we cannot deny that we are inching toward a moment in history when our relationship with technology will be fundamentally altered, as the creatures of our imagination slowly begin to take real form, and we are faced with the responsibility to not only create but also care for them.

I wonder if this is possible now. We may need it.

Ask better questions

He would come into the institute in the middle of the night—the only time when I was allowed to work—and pummel me with the most probing questions. You could tell the quality of his thinking by what he chose to ask (questions being the true measure of a man)

Having something to aspire to

“Gods are a biological necessity,” he said to me on a particularly warm night at his home in Georgetown, during that last summer when he could still get around on crutches, “as integral to our species as language or opposable thumbs.”

According to Jancsi, faith had afforded the primeval peoples of the world a source of strength, power, and meaning that modern man lacked completely; and it was this lack, this profound loss, that now had to be addressed by science.

“We have no guiding star,” he told me, “nothing to look up or aspire to, so we are devolving, falling back into animality, losing the very thing that has let us advance so far beyond what was originally intended for us.”

Jancsi thought that if our species was to survive the twentieth century, we needed to fill the void left by the departure of the gods, and the one and only candidate that could achieve this strange, esoteric transformation was technology; our ever-expanding technical knowledge was the only thing that separated us from our forefathers, since in morals, philosophy, and general thought, we were no better (indeed, we were much, much worse) than the Greeks, the Vedic people, or the small nomadic tribes that still clung to nature as the sole granter of grace and the true measure of existence. We had stagnated in every other sense.

We were stunted in all arts except for one, techne, where our wisdom had become so profound and dangerous that it would have made the Titans that terrorized the Earth cower in fear, and the ancient lords of the woods seem as puny as sprites and as quaint as pixies. Their world was gone.

So now science and technology would have to provide us with a higher version of ourselves, an image of what we could become. Civilization had progressed to a point where the affairs of our species could no longer be entrusted safely to our own hands; we needed something other, something more.

In the long run, for us to have the slimmest chance, we had to find some way of reaching beyond us, looking past the limits of our logic, language, and thought, to find solutions to the many problems that we would undoubtedly face as our dominion spread over the entire planet, and, soon enough, much farther still, all the way to the stars.

This is fascinating, especially now.

We are seeing it, for example, with the rise of communities flagging ‘e/acc’ and similar, broadcasting their techno/optimism.

It gives us sometime to aspire to.

I find that science and technology is a better god than other modern alternatives: money, status (including fame).

His analysis made no sense to me, and I said as much: there was no evidence for any of this. Billions of people still had unwavering faith in God, and their complete irrationality and incurable superstitions showed no signs of becoming weaker.

Janos did not agree: “Those gods are living dead. They have lost their glory. They cannot give sense to the world because they are remnants, broken relics that we still carry around with us, just as sickly and powerless as those horse-drawn buggies you see in the streets of New York. Just because they are still here does not mean they are of any use. We mount our warheads on the tips of missiles that can reach around the globe, we do not strap them to the backs of mules.”

I knew that Jancsi had always received from mathematics and science the sense of purpose that others obtain from faith and religion, and so I could understand how those feelings could suddenly begin to overlap and intermingle in strange ways, as he now stared into the abyss of death.

Liked these notes? Join the newsletter.

Get notified whenever I post new notes.